Notes from the Deal Room: How Buyers Protect Themselves with F Reorgs (and What Sellers Can Do About It)

The Key Family Wealth BAS team is dedicated to providing guidance and support to privately held business owners like you. Specifically, the BAS team helps owners prepare for an eventual business transition with strategies and advice on how to maximize the after-tax value of a business transition.

One of the central truths in mergers and acquisitions (M&A) work is that buyers want to buy assets, and sellers want to sell stock. A main reason is simple: 17 points. These 17 points signify the difference between the highest ordinary income tax rate of 37% and the highest long-term capital gains tax rate of 20%. The 17 Points are tax points – and, as in golf, lowering this score helps win the game for almost every business owner.

Unfortunately, sellers don’t always receive stock sale treatment. The biggest nontax reason? Buyers tend to want to pick what assets they buy (and thus what liabilities they avoid) in a transaction. The biggest tax reason? Buyers want the ability to depreciate or amortize the assets they buy from the seller over time: they want to acquire a tax shield. This article will address the questions: Why do buyers prefer asset purchases? What ways can they effect it? Are some of those ways better than others? What can sellers do about it? Enter the Subchapter F reorganization plan (F reorg, for short).

Buyer’s-eye View:

Asset Purchase vs. Stock Purchase

One main reason buyers prefer buying assets over buying stock is simple: they receive back the tax benefit of depreciation (for tangible assets) and amortization (for intangible assets). To see this, let’s compare two buyers acquiring a business. Buyer A buys assets, and Buyer B buys stock. The purchase price of the business represented by the assets and the stock is the same: we’ll say it’s $100MM.

For simplicity’s sake, let’s say the net identifiable assets of the Seller sum to $50MM, $40MM of which represents long-lived assets; these long-lived assets have an average useful life of 7 years; and their residual value is zero at the end of those seven years. Let’s also say that the Buyer’s effective tax rate is 30%. Given these facts, Buyer A has:

$40,000,000 asset value/7 years = $5.71MM of depreciation deductions for the next seven years post-sale

This results in an annual $5.71MM depreciation deduction x 30% effective tax rate = $1.71MM of annual tax savings for that time

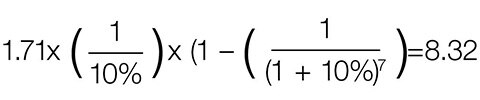

If the business has a 10% opportunity cost of capital/discount rate, the present value of this tax shield at a 10% discount rate (in $millions) is:

Mathematical equation calculation of $8.32MM of deal value.

Buyer A thus has $8.32MM of additional deal value due to the tax savings from the depreciation deductions received in an asset purchase.

Buyer A also has amortization deductions arising from the goodwill paid for the business.

$100MM total purchase price – $50MM net identifiable assets = $50MM of goodwill paid

$50MM goodwill/15-year amortization period = $3.33MM annual amortization deduction

$3.33MM x 30% effective tax rate = net tax benefits of $1MM per annum for the next 15 years

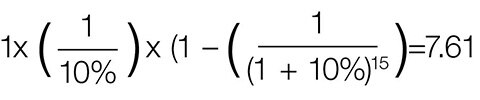

The present value of this tax shield, also at a 10% discount rate (in $millions) is:

Mathematical equation calculation of $7.61MM of deal value.

The net result is $15.93MM of tax benefit – today – that accrues to Buyer A at the moment of purchase over and above what Buyer B buys (all else the same). Given this fact, it’s not surprising that buyers want to buy assets.

What about Buyer B? Buyer B gets none of these deductions. Why not? Because Buyer B’s purchase of Seller B’s stock carries over the useful lives and accumulated depreciation of the assets inside the corporation: the buyer can’t get a basis step-up in the assets. Buyer B, however, as the buyer of the stock, does assume all of the liabilities of the seller – something few buyers want. Given these facts, it may seem surprising that stock sales ever happen, except for transactions involving very large companies. (Although there are other cases where they still make patent sense, such as when nontransferable contracts exist.)

Seller’s-Eye View:

Asset Purchase Vs. Stock Purchase

What about the Seller? What happens to them in this transaction?

The Seller to Buyer B has only long-term capital gains taxes to pay on the sale of their stock. (Depending on the circumstances, the 3.8% Medicare surtax may or may not apply; it is not used here.) Combined with an assumed average state/local tax rate of 5%, this likely means that the Seller’s tax bite on sale is 25% of the gain on their sale of the stock. In this case, if the stock is zero basis, the gain is $100MM, and the tax is $25MM. The seller nets $75MM.

Contrast this with the Seller to Buyer A. If we assume zero basis on the long-lived assets, $10MM basis on the net working capital items (mainly net receivables and inventory), the highest ordinary income tax rate of 37%, and the same state rate of 5%, we have:

$0 gain on net receivables and inventory (assuming accrual-based accounting)

$40MM ordinary gain on long-lived assets, with a tax of $16.8MM

$50MM of long-term capital gain, with a tax of $12.5MM

Total taxes: $29.3MM

Net to Seller: $70.7MM

From this, we see that the seller clears $4.3MM more in the stock sale than the asset sale. Combined with the asymmetry seen before from Buyer A’s tax shields, the asset sale provides ~$16MM of incremental benefits to the buyer, and $4.3MM of incremental costs to the seller.

Enter the F Reorg

From this, it again becomes clear: buyers want to buy assets, and sellers want to sell stock. Prior to the F reorg, there were two elections that buyer and seller could make to take the most undesirable aspect of a stock sale – the loss in tax basis to the buyer – and eliminate it. These were the Section 338(h)(10) and 336(e) elections, which gave buyers of stock this tax shield back. The main challenge with these provisions was that they required an acquisition of 80% or more of the business. Enter the F reorg.

F reorgs permit the buyers of S corporations the ability to obtain:

The step-up in basis of the corporate assets they’re purchasing

The ability to offer tax-free rollover equity treatment to target shareholders, even without buying 80%+ of the company

More flexibility than a Section 338(h)(10) or Section 336(e) election, which also create asset sale conditions around what is effectively a stock sale

Here is an example of an F reorg in action. Suppose you have an S corporation shareholder with a $100MM business. The owner is the sole shareholder and is approached by a private equity group (PEG) that wants to purchase the company. The main stipulation? The owner must be willing to execute a specific transaction with the PEG to consummate the deal. This owner must execute an F reorg.

This is what the S corp shareholder has to do:

Create a new holding company (NewCo).

Contribute all of the shares of the existing operating company (OpCo) to NewCo in exchange for 100% of the stock of NewCo.

Make a qualifying Subchapter S subsidiary (Qsub) election for OpCo.

Create a separate single-member LLC with the same ultimate owner as OpCo.

Merge the QSub into the LLC.

Sell the LLC units to the PEG, whether for cash, shares in one of the PEG’s funds, or other consideration.

Why is this of such interest to the PEG? There are several reasons:

First, the PEG wants to be absolutely sure it acquires the aforementioned tax shield that attends the purchase of assets from the seller. To do this, it has to ensure that the transaction is treated as an asset purchase. The F reorg fulfills this requirement.

Second, the PEG wants to make sure that the shares of the business it buys aren’t actually C corp shares posing as S corp shares – in other words, that they don’t end up buying a C corp because someone failed to ensure the corporation’s S election. What if this were to occur – that is, what if a buyer thought they were buying S corp shares, but were really buying C corp shares? The entire step-up in basis and ensuing tax shield would be lost, and the basic tax reason for the buyer to pursue the transaction would be destroyed. These transaction exertions help avert this problem.

Section 1202 and the F Reorg

There are permutations of the F reorg that, when combined with other provisions of the tax code, can result in interesting possibilities. What if a seller undertook all of the steps for the F reorg, but subsequently either buyer or seller got cold feet? What if interest rates spiked and the deal got shelved? If this occurred, an owner might consider establishing a new C corp and then contributing the LLC interests to it. If certain conditions are met (see our previous article on Section 1202 here), the greater of $10MM or 10 times the adjusted basis in the C corp shares could potentially be eliminated on sale. Since the maximum assets at the time of the inception of this new C corp to qualify for §1202 are $50MM, this means that, were the stars to align, the owner of a C corporation meeting all of the Section 1202 requirements could (again, potentially) create as much as $500MM of nontaxable gain.

Conclusion

The existence of so many structural permutations in the private M&A world necessitates an advisor who has a seller’s countermeasure for every buyer-proposed concession. In the example above with our Buyers A and B, what could Seller A do to get a deal with a result more like that of Seller B? Seller A’s advisor might suggest that Buyer A gross up the purchase price so that Seller A nets the same $75MM that Seller B received. An even more accretive move would be to further negotiate for part (or even all) of the $15.93MM tax shield that Buyer A receives onto the purchase price. (Is it fair to negotiate for all of this tax shield? In general, once the LOI/term sheet has been signed, no. But prior to this, these items are common negotiating points when deal structures change.) In the sell-side advisory space, familiarity with provisions like the F reorg is table stakes for those who want maximum consideration for their businesses – and to minimize their exposure to the 17 Points.

For more information, please call your relationship manager.