Key Questions: Private Equity: What Else Do I Need to Know?

The Key Wealth Institute is a team of highly experienced professionals representing various disciplines within wealth management who are dedicated to delivering timely insights and practical advice. From strategies designed to better manage your wealth, to guidance to help you better understand the world impacting your wealth, Key Wealth Institute provides proactive insights needed to navigate your financial journey.

Public equities are fairly simple to invest in: Open an account, search for a security, buy the security, and watch real-time price moves. In contrast, private equity is fairly complex.

There are a number of private equity-specific nuances and terms (bolded throughout) that require understanding before building a private equity portfolio. This article addresses the structural elements of private equity that differ significantly from more traditional investment vehicles.

Who Can Invest in Private Equity?

Private equity comes with increased risks, so the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) restricts access to a select group of investors. Generally speaking, private equity is only available to qualified purchasers, or individuals with more than $5 million in invested assets. In some cases, however, accredited investors with over $1 million net worth or annual income exceeding $200,000 may also have access.

How Does a Private Equity Fund Work?

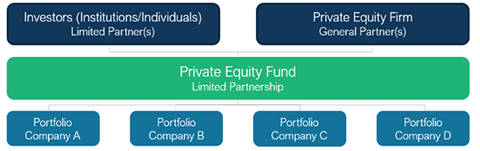

During its marketing phase, a private equity firm (also known as a General Partner or GP) collects subscriptions from investors for a given fund (also known as Limited Partners or LP). Fundraising lasts until the fund reaches its target size (or somewhere close to that amount). For example, a private equity fund may seek capital commitments for a $500 million fund. Capital commitments are just as they sound — a legally binding commitment from an investor to invest a specified amount of money into the GP’s fund.

The fund is raised with a stated strategy in place, such as making 10–15 controlling investments in North American, middle market companies. However, investors won’t typically know the exact construction of the fund beforehand — this is why a private equity fund is commonly known as a “blind pool.”

visual depiction of a typical private equity fund structure

Once the fund raises a sufficient amount of capital, it holds an “initial close,” when the fund commences operations and begins making capital calls (more on that below). In many funds, the fundraising continues for a period after the initial close, ultimately culminating in a “final close,” after which fundraising is complete. The year of the first investment is known as the “vintage year,” which can be useful in comparing relative performance of private equity funds against each other or the public markets.

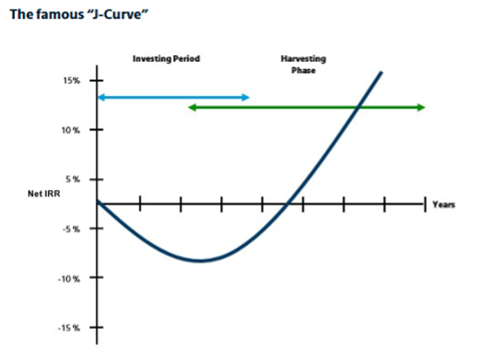

Private Equity Cash Flows: Capital Calls, the J Curve, and Distributions

After fundraising, the fund enters the investment period. During this time, the fund requests its investors to send portions of the committed capital to fund each new investment. These are known as “capital calls.” The investment period generally last several years, allowing the private equity firm to search diligently for appropriate and compelling investments. Because of this, in the first several years of a private equity fund, investors should anticipate outflows with minimal realized or unrealized gains. Additionally, annual management fees (often 2%, but more on that below) are paid on committed capital, rather than called capital, resulting in negative returns in the early years of a private equity fund. This profile of returns is known as the “J curve,” as pictured below.

visual depiction of the private equity J-curve, which shows how fund-level internal rate of return (“IRR”) varies through the fund life

After the initial investment period, the fund also begins its efforts to create value for its investors. These may be of upgrading management talent, introducing new products, entering new markets, or acquiring other companies. This is where the highest-quality private equity firms stand out from competitors; the premier teams have a reliable playbook to drive earnings growth on behalf of their investors.

Once value is starting to accrue, the fund enters the “harvest period,” in which the fund begins to realize the value of its investments. It is at this point that investors begin to receive distributions from the fund.

Private equity funds also often have the option to extend the fund for one-year terms (often two terms) via extensions. These are generally exercised when the General Partner feels that significantly more value can be created with additional time. This could reflect poor market conditions for exiting an investment or simply additional time to improve the fundamentals of the underlying investment. Extensions typically must be approved by the Limited Partners.

How Do Private Equity Fees Work?

Investors in private equity funds are typically charged a management fee and a performance fee. The management fee is just as it sounds — it is an annual fee (typically 2%) to compensate the GP for managing the investment throughout the life of the fund. It is important to note that management fees are generally charged on committed capital during the investment period, and then 2% on invested capital thereafter. For a very simple example, on a $1 million commitment, a Limited Partner should expect to pay $20,000 per year through the life of the fund.

The performance fee, also known as the incentive fee or carried interest, creates a strong alignment between Limited Partners and General Partners because both parties are incentivized for the GP to significantly increase the value of its investments. Performance fees (often 20%) are charged on the increase in the value of an investment, subject to a hurdle rate, also known as the preferred return. For example, a fund may employ a 20% performance fee over an 8% hurdle rate. This mechanism is known as the distribution waterfall, and may be most easily understood through a simplified example.

Fund A bought Company 1 for $50 million in 2015 using $10 million of equity and $40 million of debt and sold it for $100 million in 2020, resulting in a $50 million gain for the Fund. Fund A charges a 20% performance fee over an 8% hurdle rate.

- First, the debt ($40 million) is paid back, leaving $60 million of equity.

- Next, the hurdle rate is established – on $10 million of equity over a five-year period, the equity hurdle would be $14.7 million (8% return, compounded annually). From the $60 million of equity in the last step, $45.3 million remains.

- From this pool, the General Partner receives 20% ($9.06 million) and the investors receive the remaining 80% ($36.24 million).

As seen in the above, the performance fee is the overwhelming majority of compensation for the General Partner, again highlighting a strong alignment between the GP and the LP.

How Is Private Equity Performance Measured?

Private equity performance is measured in a unique manner relative to public markets. The primary performance metrics are the internal rate of return and multiple on invested capital. It’s worth noting that both measures can be presented on a gross (before fees) and net (after fees) basis. It is also important to consider both of these factors together, as neither metric on its own is sufficient to evaluate performance. The nature of private equity is such that investors need to consider dollar return and timing, as the GP controls the timing of investment decisions.

The internal rate of return (IRR) is a measurement of cash outflows and inflows that is equivalent to the annualized rate of return, but considers timing and dollars generated. All else being equal, a fund that quickly returns cash to its investors will have a higher IRR, whereas a fund with modest returns over a longer period will have a lower IRR. Investors typically seek IRRs of 15% to 20%,, though this can vary significantly based on the fund’s investment strategy. In the example above, the specified investment would have a gross IRR of 14.8% ($100 million divided by $50 million, annualized over five years).

On the other hand, multiple on invested capital (MOIC) purely looks at the value of the investments today compared to the original investment value, regardless of the timing of cash flows. It is measured simply as the total value of investment inflows divided by the total value of investment outflows. As with IRR, a higher MOIC multiple indicates better performance. Using the example above, the gross MOIC would be 2.0x (simply $100 million divided by $50 million).

While IRR and MOIC are relevant for comparing private equity funds against other private equity funds, an additional step is needed to evaluate private equity versus public markets. This is accomplished using a public market equivalent (PME) method. While there are several ways to do this, the most simple method is to evaluate each cash flow (capital calls and distributions) as a theoretical investment in a public index.

Using our above example, suppose the relevant benchmark is the S&P 500 Index. Imagine deploying $50 million into the SPDR S&P 500 ETF on January 1, 2015, at a price of $205 per share. On January 1, 2020, the holding could have been sold for $322 per share, or $78.5 million; this equates to a theoretical gross IRR of 9.5% and gross MOIC of 1.57x. By evaluating these hypothetical metrics with the private equity returns, we can see that private equity would have outperformed the public markets.

How Will Private Equity Affect My Taxes?

There are two main tax consequences for investors in private equity to be aware of. First, investors receive a Schedule K-1 due to their ownership interest; investors are taxed on their share of the fund’s profits or losses. Second, because private equity reports on a lagged basis (often up to six months), investors may need to file for a tax extension. It is best practice to consultant a tax advisor when investing in private equity.

Conclusion

Private equity can have significant benefits for a portfolio in the form of potentially higher returns and diversified exposures. On the other hand, private equity is more complex than public equities, both in its structure and its terminology. An investor should fully consider the role of private equity in their portfolio, namely the illiquid nature of the strategy, the levered nature of the underlying investments, and reduced visibility. By understanding these elements in greater detail, investors can better focus their evaluation of private equity on investment merits and considerations.

For more information, please contact your advisor.